Ungulate Highways

In search of mountain caribou in Idaho's Selkirk Mountains

Author: Jack Kredell

Published: Summer 2025 Issue

Ungulate Highways first appeared in Storying Extinction, a multimedia project built by Jack Kredell, Christopher Lamb, and Devin Becker. Kredell worked with The Westrn’s editors to shorten the written piece for our publication. To see the entire project, visit the Storying Extinction website.

My fascination with nonhumans, particularly those who are extinct or out of reach — dinosaurs or abyss-dwelling giant squid — reached a fever pitch when I encountered a being who, until that moment, was known to me only from the pages of my encyclopedia and the museum.

Early one morning, my dad woke me up and carried me, half-asleep, to the bay window in the living room and whispered, “Look.”

All I saw was a blur of glaring light as I wiped the sleep from my eyes. Drenched earlier by my dad’s ritual dawn watering, the grass blazed and shimmered in the early morning sun. Slowly, the front yard took on its familiar shapes — the two sycamores with their fuzzy leaves and pastel trunks, the hedge with its clusters of white, bee-loving flowers. Then I froze (in some far-off world, I am still holding that breath): a long brown neck bent gracefully toward an island of dandelions. An animal — a deer. A deer was standing in the front yard of our suburban San Fernando Valley home.

It was my first time seeing real megafauna outside the articulated skeletons dredged up from the La Brea Tar Pits on display at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. My pulse quickened and my body ached to get closer. Wanting to see it without the dark-tinted mesh of the window screen, I ran to the front door and stuck a hand through the mail slot to lift the faux-brass door, but as I did, the hinge creaked and the deer bobbed its head, spun, and bounded away up the street. As much of me died in that instant of departure as was made alive by the arrival.

I say “bounded away up the street” but I don’t know where the animal actually went. It disappeared into the landscape as only deer and other ungulates can. They ghost. They get on their ghost highways and vanish. Though suburban deer aren’t too uncommon, it was a miracle to me at that age. It’s also my earliest memory.

I’ve replayed the episode of my dad waking me to see the deer countless times in my head. It’s one of the stories I associate with the San Fernando Valley, and yet, it is just as much a story about a different time and place, infused by later childhood years when I’d stalk white-tailed deer in the hardwood forests of central Pennsylvania.

In that encounter with the deer I was seized. “As we are seized,” write Thom van Dooren and Deborah Bird Rose in “Lively Ethography,” “so we bear witness in order that others may be seized: telling stories that draw their audiences into others’ lives in new and consequential ways, stories that cultivate the capacity for response.”

The encounter with the deer is the story of my becoming seized, of bearing witness to a shared world. It is simultaneously the response — unfolding over my lifetime from that moment until now — of ungulate dreams.

II.

I first heard of South Selkirk mountain caribou while driving from New York City to Idaho in search of a different ungulate — elk. I held a nonresident archery elk tag in my pocket and would try to fill it while visiting my grandmother in Donnelly, Idaho. It was late in the summer of 2016 and I’d just quit my job of three and a half years at a tech startup, a job which, in addition to low pay, gave me chronic lower back pain but no health insurance or time off to fix it. I didn’t know or care what was next. I just knew I needed a month of climbing mountains, grand views, shitty coffee, pumping gas, freeze-dried meals, cold nights, tired legs, and missing home, as opposed to standing in crowded subway cars full of bruised and angry rundowns like myself. Most of all, my back needed time off from sitting. The irony wasn’t lost on me either: I would spend the next five days in the driver’s seat.

My snot-green 1998 Jeep Cherokee stereo played a hunting podcast in which the episode’s guest, Bart George, a wildlife biologist for the Kalispell Tribe, discussed the tribe’s effort to save the South Selkirk mountain caribou herd, then estimated to be fewer than 15 individuals. Despite the alarming precarity of their situation, I was awestruck by the thought of caribou actually existing in Idaho and Washington. I became seized by caribou and their otherness with respect to the ungulate scene of the United States, which includes deer, sheep, moose, mountain goats, pronghorn, and elk.

The thought of caribou took me to another era — the Pleistocene epoch of my beloved La Brea Tar Pits. As a child, I longed to be among its extinct dire wolves, short-faced bears, and saber-toothed cats. I came to think of mountain caribou as an ice age phantom, a relic, a ghostly projection from the ancestral Cordilleran ice sheet. Part living, part dead.

In fact, the continent was already full of their ghosts; the recent extirpation of mountain caribou wasn’t a first for caribou in the history of the United States. We’ve witnessed a second death.

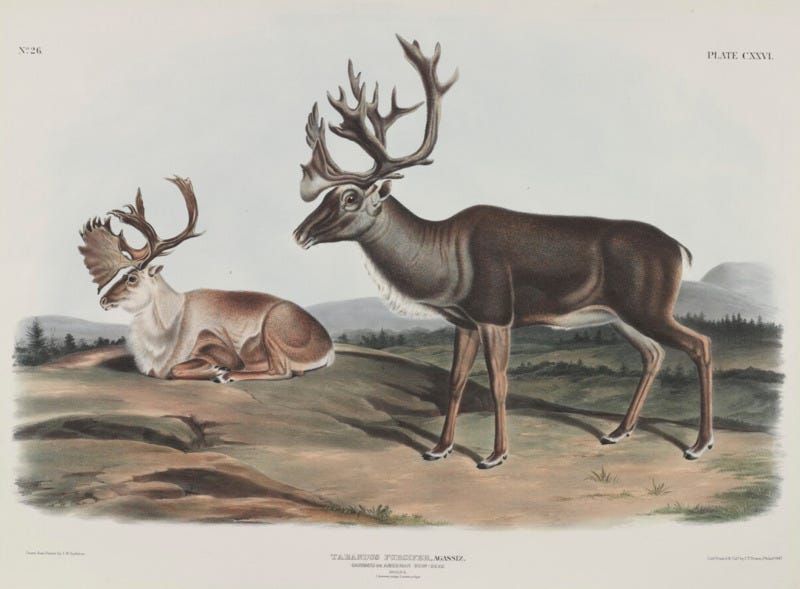

Until the mid-19th century, woodland caribou — a boreal forest-dwelling subspecies of North American caribou (Rangifer tarandus) — ranged as far south as Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and New England. Unlike their migratory Arctic cousins, the barren-ground caribou, these were mostly sedentary animals who for millennia lived and died in the coniferous snow forests of the northern United States.

Today, certain northeastern toponymies bear witness to woodland ghosts. Maine’s Caribou-Speckled Mountain Wilderness, for example, is named after two brothers who shot and killed the area’s last caribou in 1854. With the exception of a few individual animals spotted in northeastern Minnesota during an aerial survey in winter of 1980-81, woodland caribou were all but eliminated in the contiguous United States by the start of the 20th century. However, southern mountain caribou — an ecotype of woodland caribou once also called ‘black’ caribou due to their dark, shadowy appearance — still occupied the northern tip of Idaho's rugged Selkirk Mountains as recently as 2019, though their presence remained tenuous and beleaguered.

The mountain group outlasted its woodland relatives by migrating, not to colder far northern latitudes, but to colder altitudes in the South Selkirks of Idaho and Washington. Here and in other ranges where they lived historically — the Purcells, Cabinets, and to some extent the Bitterroots — mountain caribou adapted to a life of wintry high-country solitude. Now, due to a combination of factors including large 20th-century fires, resource extraction, development, and an increased load of winter recreation, the South Selkirk mountains were no longer an oasis.

In the spring of 2019, news broke that officials airlifted the South Selkirk herd’s remaining three individuals to a captive breeding facility in southern British Columbia, leaving them functionally extirpated. That fall I entered grad school at the University of Idaho where I began asking myself a set of questions: What was their story, I wondered, and how does one even begin to tell the story of extinction? What does their extinction mean to us? What does it mean to the people who knew them through their encounters?

III.

Do you have an Idaho caribou story?

We are a pair of University of Idaho graduate students currently at work on a research project about the recent loss of North Idaho’s South Selkirk mountain caribou herd. We will be traveling to the South Selkirk Mountains and surrounding communities to gather ecological, historical, graphic, and geographical data that will be incorporated into a web-based deep map (multilayered interactive map) documenting ecological/community response to mountain caribou absence in North Idaho. A key component of this project is the collection of oral history from communities surrounding this area. We are seeking volunteers who have stories or encounters pertaining to the former Idaho Mountain Caribou herd for incorporation into the project.

A week after publishing our call for caribou stories in the Spokesman-Review we got a terse email from somebody named Bob Case:

On June 14, 2020, at 2:56 p.m., Bob Case wrote:

I have pictures of a caribou encounter.

Sent from my Samsung Galaxy, an AT&T LTE smartphone

We agreed to meet Bob two weeks later in a parking lot. It’s starting to drizzle when he pulls up in a navy-blue Subaru Baja. He’s short, middle-aged, and wearing a pair of dark sunglasses despite it being overcast and rainy. He greets us in a strained, screechy kind of whisper which he informs us is due to a chronic condition called laryngeal dystonia where muscle spasms prevent the voice box from operating properly. Though it seems painful, it’s apparent right away that Bob loves to chat.

Without missing a beat and like some old-fashioned gumshoe, Bob unwinds the string fastener on a manila envelope and begins to narrate as he places a half dozen original photographs of a large mountain caribou bull on the bed cover of his Baja. Despite having used a miniature format 110 camera, the pictures of the massive radio-collared bull standing broadside in a Selkirk boulder field are otherworldly. They communicate both a sense of proximity to and respectful distance from the animal.

We attach the Lavalier mic to his collar, turn on our camera, and witness as Bob sings:

“I’m Bob Case and I took a hike up to Chimney Rock. I want to say it was either ‘93, maybe up to ‘95. Somewhere in there. And when I went up over this ridge, an open rock field, which you can see right in here [points to his photograph of the caribou in a rock field], I came down, I was walking down, and then this caribou stood up. Well, the people told me about being careful with the encounters with the different animals that could charge ya, and I said, well, they never told me about this [points demonstrably to caribou photo ]— what this could do.

“So I stood there and looked for an area where I could dive under the rocks to protect myself and got my camera out and started taking pictures. Then the caribou got up and it walked around just like this [now Bob is doing something with his hands that reminds me of an orbital model of the earth and moon. Bob and caribou are celestial bodies at this point, orbiting one another in the shared gravity of encounter] and it got closer and closer as it walked. When it got here, I believe it got the smell of me with the wind blowing and then it just walked off. So that was my day and I got to see a caribou and I been hiking ever since because that was the biggest thrill ever since I been hiking here.”

Afterward, I wasn’t sure if Bob had encountered a caribou or if a caribou had encountered Bob.

Later in the summer, we spend time with a subject who spent a decade trying to get a glimpse of a mountain caribou in the wild, without success, and here is Bob, the translocated Bostonian, wondering if he should dive under the rocks to avoid the charge of a radio-collared and translocated bull caribou, at the time the most critically endangered mammal in North America. In the video, Bob appears to get emotional during the last sentence. As he says, the encounter that day with a radio-collared bull caribou “was the biggest thrill ever since I been hiking here.” This statement still resonates with me, because of both the significance of the encounter for him personally and his complete lack of interest in the radio-collar as well as the politics surrounding the herd augmentation effort. For Bob, it was an encounter with something magnificent that could “charge ya.” It simply happened to be a mountain caribou.

His encounter story is a bearing witness to caribou, which are now absent from Idaho, but it is also a bearing witness to ourselves in terms of asking what world we choose to inhabit. Do we want to live in a world in which “this“ — Bob’s word for caribou because miracles do not possess taxonomies — cannot seize us in some alpine boulder field? Cannot make us want to dive under the rocks when faced with its nameless and terrifying beauty? Do we want to live in a world in which a deer can’t walk out of the pages of a child’s tattered encyclopedia? I am that child and because of that deer I now walk the ungulate highways in search of caribou ghosts.

I feel a strong kinship to Bob. As a child, an uncontrollable stutter caused my voice to seize and trip over itself, making it uncomfortable to talk. So I avoided people and instead sought the company of animals who relieved me from the burden of speech. They were gracious and let me practice my solitude beside them. There, I learned to sing with them. For an animal is a song, a specific reverberation of space and time that echoes and harmonizes across van Dooren and Bird Rose’s “countless interwoven ethea that together comprise the foundation of our worlds.”

I am beginning to think the song of mountain caribou in the lower 48 has ended, or is in the process of being forgotten. Extinction is a kind of forgetting.

IV.

While sitting face to face with an interview subject, I often think how I am looking at eyes onto whose retina appeared, inverted, and bore human witness to the image of a real mountain caribou. A physical trace now exists in their brain as the encounter’s dendritic signature. And as they talk, I feel the image of the mountain caribou migrating from their brain to my own, from their solitude to mine.

Greetings,

I may have some information relevant to your caribou research project.

Don’t hesitate to contact me.

Dave Boswell

I didn’t hesitate, but the call went straight to voicemail. A few hours later, while eating Chinese takeout, I got a call from a Spokane number:

“Hi, is this Dave?”

“Are you the caribou guy? Which one are you?”

“I’m Jack.”

“Well nice to meet you, Jack. My name is Dave Boswell. So you guys are putting together some kind of project about mountain caribou?”

I tell him about how we are building a digital deep map; a multimodal and interactive spatial narrative about caribou loss told through video and audio interviews, ecology, photography, and getting ourselves lost in the woods. The loss of a species is the loss of a world; a world that is mappable insofar as it is understood to be lost. We were going to map their absence. Gone is the starting point.

“Are you guys natural resource majors?”

“No, English.”

“Well shit, that’s weird. Have you ever heard of the Jeannot Caribou? It was shot by Jean Jeannot in 1892 and the mount was exhibited in the 1893 World’s Fair wherever it was that year.”

“Chicago?”

“It was the largest black caribou ever shot in the state of Idaho. I use the term ‘black caribou’ on account of their dark coloration. Long story short, I found two caribou mounts at a hotel saloon in Hope, Idaho and bought them. The smaller one I gave to the biologist Don Johnson at the University of Idaho. He wanted the jawbone for something. He measured the Jeannot caribou and said it was the largest specimen he’d ever seen. Hold your arms out wide as you can. That’s how big it was.”

I envisioned filming Dave sitting by the fireplace with a glass of merlot, the Jeannot caribou mount resting beside him, telling the story of how he, against all odds, rescued the internationally famous caribou from Hope, Idaho. I asked him if we could come see the mount and get his side of the story on camera.

“It’s in the basement at my place near Priest River. But it’s a sad story. Some teens broke into my cabin a while back and stole the antlers. Stole some other stuff too.”

“They sawed them off?”

“No, they used a fire poker to hack them off. You guys want to come spend the night at the cabin?”

I immediately called Chris to tell him about the enigmatic caribou aficionado who invited us to spend the night at his cabin in order to see the Jeannot caribou which, unfortunately, had been mutilated by teenagers and was now kept in his basement. Chris agreed without hesitation to spend the night at Dave’s remote cabin, the risk of visiting a stranger’s remote basement be damned.

In the weeks leading up to our visit, Dave becomes a mythic figure to us. He’s a true disciple of the gray ghost, a mountain hermit who wandered the Selkirk wilderness for a decade only to fall short of glimpsing his idol. The closest he got was a set of tracks at a place called Goblin Knob.

V.

Dave, holding a glass of wine filled beyond decorum, and his neighbor, Phil, come out to greet us. Dave’s voice is booming and sonorous, its intonation flecked with a pleasing grit. When he speaks, which is often, his backwoodsman’s penchant for a profanity-laced tirade is executed with the flair and verbal resources of an urbane lawyer (Dave practices at a small firm in Spokane). He wears blue jeans with suspenders and a white linen shirt, the front beginning to untuck itself. Pale blue eyes are deep set under white eyebrows. His shoulders are still broad, presenting an imposing figure despite being well into his 70s.

Phil is younger by a decade, mild-mannered and soft spoken. Phil’s T-shirt has the name of a conservation organization on it and features a tableau of African wildlife — zebras, rhinos, wildebeest, impalas, giraffes and elephants. His long hair is kept in a ponytail which has a beautiful sheen to it. He’s just been through a divorce. I immediately like him.

We move on to a larger cabin built by Dave and his brothers. The interior is dusky, storybook-like, and smells lushly of cedar. Our camera recording, Dave becomes uncharacteristically demure about his own encounter with mountain caribou, which in fact never took place. Chris and I make a dent in our bottle of whiskey. Dave takes a big gulp of wine. As I told him over the phone, we’re interested in precisely what you didn’t see and how that felt. He looks at Phil. Phil, however, looks at me and I realize we’ve got Dave where we want him. He is getting ready to sing.

“Phil, I told you these guys were crazy.”

Dave tells the story of how for 10 years he tried and failed to see a black caribou in the wild. He spent a decade going up and down the gnashing serrated teeth of the Selkirk crest on snowshoes. But to no avail. He saw tracks but never the ghost itself. Chris asks him what he thinks it would have been like to see a caribou. Dave smiles, repeating the question back to Chris.

“What would it have been like to see a black caribou in the old growth spruce forest on top of the Selkirk crest? If you were agnostic, you’d reconsider because God has just exposed his face to you.”

We lose the light and decide to film the same session again in the morning. We move back over to the first cabin and drink even more beer as Dave prepares a stir fry dinner.

“Hey,” says Dave, “You guys wanna see the Jeannot caribou?”

Phil yanks open the cellar door and gestures for us to enter like a maitre d pointing to our table. I see Chris hesitate, ducking his head under a crossbeam. The basement is illuminated by a single overhead lamp which casts an orange hue on everything. We’re all standing in front of a washer and dryer. On top of the washer sits a caribou shoulder mount-sized object covered by a black trash bag.

“Phil, why don’t you go ahead…”

And then we saw it — the worst example of taxidermy I’d ever seen. The Jeannot caribou now cosplayed as a hay-stuffed sock puppet with gouges in its head where antlers should have been. Instead of dark and depthless tan and black shadows cast by old growth canopy, its coat was the color of a Ritz Cracker. The frayed skin flap of the lower jaw had completely detached. Phil was using it to make the caribou talk like some profane and dilapidated Muppet.

“You guys want some caribou hair? It’s hollow. It’s so buoyant they used it to make life jackets in the first World War.”

Dave gives us each a pinch of formaldehyde-stained hair. My mind goes to the sinking of the Lusitania, and I picture the survivors bobbing in the cold Atlantic in life jackets made from dead caribou. Then, Phil mercifully places the abomination back in its trash bag. Chris and I go up for air. We need it.

We emerge to twilit skies. I feel the bowl of the meadow and its million buzzing insects begin to slowly tilt as I realize how drunk I am. Dave and Phil make their way to bed. We pour ourselves a Scotch from Dave’s liquor cabinet and find our way to the porch, which I promptly fall off, into the soft grass. Neither of us knows what to make of what just happened, other than it being an encounter.

Later that night, in our star-studded vortex of drunkenness, we spot a curious object in the heavens. It was like a star, except blurry and more massive in size. This blurriness, we established, was not our fault, but due to the object being covered in a kind of luminous mold — making it brighter than any other in the sky. Strangest of all, it had a tail. Then, it dawned on me: Comet NEOWISE looked close enough to reach up and grab.

If only we could snatch the comet’s tail, hack it off in the spirit of teenage vandals, and bury it high up in the final place where the last caribou in the South Selkirk mountains made its home, then the black caribou would come back.

But I am too drunk to stand on Chris’s shoulders.

Are there mountain caribou in the South Selkirk mountains of Idaho right now?

We begin to laugh thinking about the ‘face of God’ but neither of us know what the face of God looks like.

Jack Kredell is a hunter, writer, and PhD candidate in Environmental Science at the University of Idaho. His research examines the wildfire crisis through its emotional, ecological, and institutional dimensions. He has collaborated on digital environmental projects including Storying Extinction: Responding to the Loss of North Idaho's Mountain Caribou and Keeping Watch, which document environmental change in rural Idaho and the western United States.