The Spring Calf

Things aren't always what we assume.

I’m driving down Highway 12, heading southwest from Missoula. Summer is settled deep into the curves of the highway and the Lochsa River at its side. The sky is cornflower blue at the edges of the trees, white blue above, sun holding court.

This particular stretch of the highway is 134 miles long, looping through ponderosa and cedar pine forests. At one point, you can walk among 2,000-year-old western red cedar so gargantuan you might squint and think you’re looking at redwoods. How many people have these trees sheltered during these years of biblical proportion, I wonder as I walk among them.

This grove was named for western historian Bernard DeVoto 61 years ago, less than 3 percent of the coniferous elders’ lifespans. DeVoto spent the majority of his years far from these trees, educated in fine east coast institutions, then tucked into a New York City apartment.

Arm out the window, I can feel my skin boiling a mahogany brown. I look at my paler arm and wince. But, there’s no rolling up the window on a day like this. I’m meeting my sunnier friend Kym in Stanley, Idaho to romp around hills and swim in Redfish Lake. It’ll even out.

I also have to pee. Real bad. I pass junction after junction, little brown vault toilets, gas stations, and bushes just the right height to run behind for quick relief.

The Lochsa is low and punching at a normal summer weight. Liberated teens jump off rocks into deep glacial blue pockets, adrenaline junkies kayak through rougher parts, anglers on the fly do their ribbon dance between water and air. Along this crystalline waterway are little beaches with soft, river-scrambled sand reminiscent of ocean edges.

I’m looking for that sort of sand on my stop. Perhaps I can close my eyes and hear ocean waves in the river.

I’m about to burst. I turn a corner and see a small stretch of beach and a brick-brown building, promising relief. I run to the vault. Then, to the water.

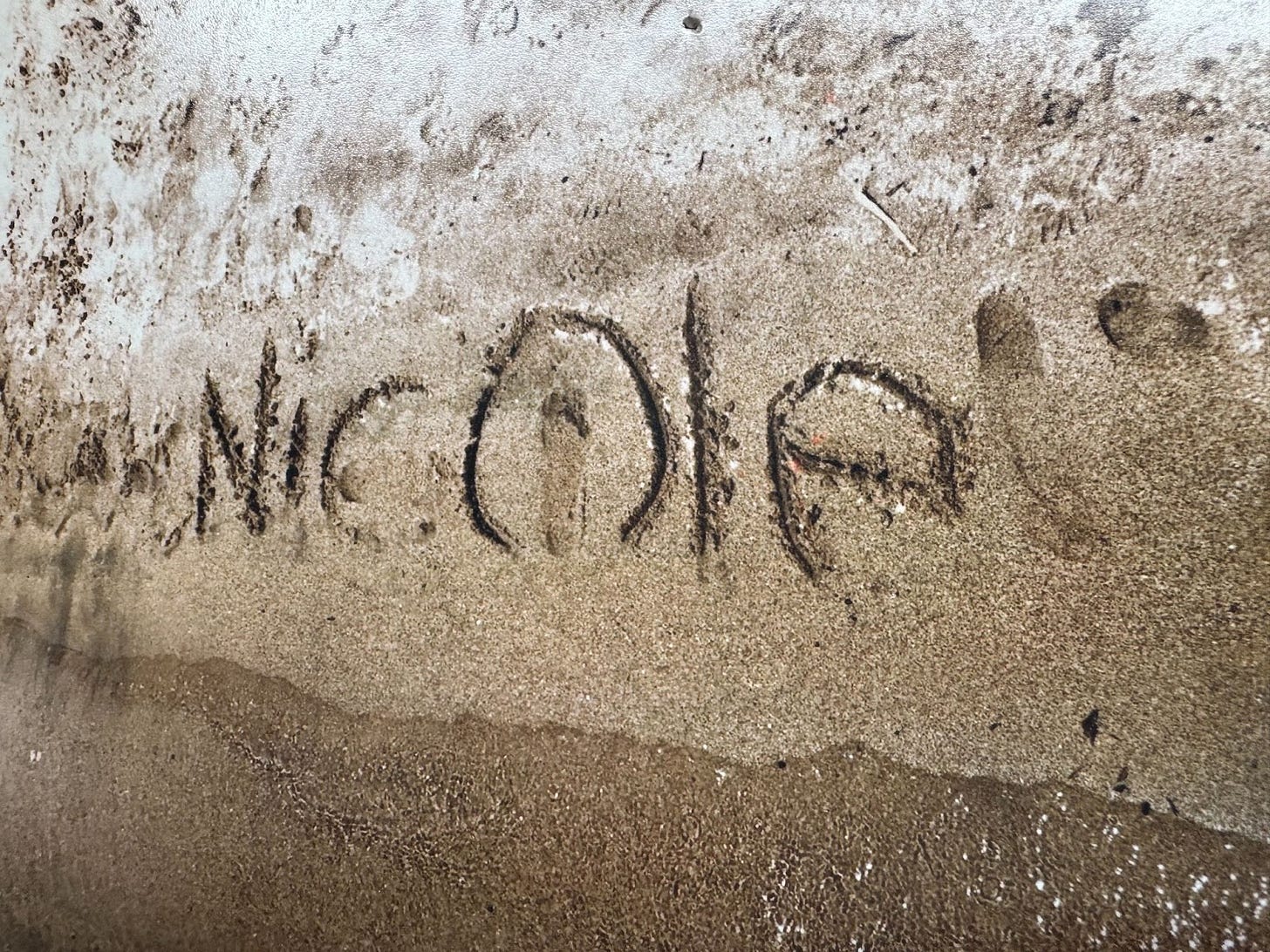

For the moment, I have the sandy break to myself. I throw off my Tevas and imprint my footsteps across the shoreline. Out of the corner of my eye, I spot a single word written in the sand. I toe over to read the writer’s work.

There, with the river lapping against the edges, my name is written in large capital letters: N I C O L E. Two footprints sit against the edge of the “E,” child-sized.

I do what I can. I stamp my own feet on the opposite end, at the N, then sit and watch as the river erases a two-for-one Nicole back into its grip.

I’m on the way to watch my good friend Kristen show her horse when I get a call from her.

“A cow is giving birth, right near the roadside, before you get to the showgrounds!”

Kristen is an emergency room doctor, no stranger to the miracle of new life. Her excitement feeds mine; my eyes are peeled.

The tension builds as I get closer to the show, watching the long lines of fence where the cattle graze and await their fates. As I turn a corner, I wave at a farmer heading out of one of the fields. He nods, a grimace on his face.

I look in my rearview mirror, and there, a black Angus heifer slumps dead against the flatbed of his truck, head lolling over the truck edge, tongue out, eyes wide. There’s no calf in sight.

I hold my breath, my heart, my stomach. I don’t tell Kristen when I get to the show.

I’m not much for swimming in the ocean, at least any further than I can touch. And that’s just what I do on a 92-degree day in Edisto Beach, South Carolina.

The dance I love is the one where you go from towel to ocean, towel to ocean, until you simply can’t stand the turn from wet to dry anymore. Hot then cool, pruny then salt-sticky. I try to tuck in between people who look reputable, families with sand castle molds or older folks with umbrellas who might say something if someone tries to swipe my bag while I’m in the water. I smile and wave at my neighbors politely as I set up my spot. Safety in recognition and numbers.

I sidle in, up to my armpits, where I can loll with the promise of sand not far from toes. The water is murky, warmer than I expected, and full of action.

A little baitfish jumps directly in front of my face, and something bigger swipes against my leg in the chase. If I stare across the top water, I catch schools of tiny fish jumping and running. The angler in me wishes I had a rod; bigger fish are most certainly moving the smaller guys around.

I stand on my tiptoes to watch for fish in the waves as they roll in. After a few minutes, not 8 feet away from me, a 6-foot spinner shark jumps straight into the air above the ocean, baitfish snapped in jaws, his tail clearing the water with room to spare. The power of his spin sprays water over my sun-baked face and his bellysmack back into the water sends a second splash.

Wide-eyed, I look back to the beach. Eyes in books, hands building castles. This moment seems to be mine and mine alone. I tread back a couple feet, but stay in the water, eyes trained east so I don’t miss the show.

Eventually, I tumble back up the beach, splay out on my towel, and begin slathering myself in SPF.

“That,” an elderly bronzed gentleman to my right says, “was a pretty close call.” He speaks without lifting his eyes from the book, turns the page, then glances over.

We meet eyes and laugh. Over the next few hours, spinner sharks revel in the abundance of the running minnows or mullet, hovering over the water for elegant and whirling split-seconds, within touching distance of the families at play. I stay and watch until I can no longer bear the heat.

I am nearly back to my car after a hike to St. Mary’s waterfall in East Glacier. The water rolls far enough behind me for the roar of the falls to have softened. Through the tall pines, the towering peaks of the park take up the edges of the sky. At my feet, dried rocks the color of pale jewels dot the dirt path.

My failing knees force me to look down as I hike. I watch for roots or rocks that, in a misstep, could jam the bone spurs of my joints against raw spots of soft tissue. I focus on the trail to avoid the jarring pain. In this sort of noticing, I see that people have built little cairns along this trail, and it’s driving me insane.

I kick them over as I go. The trail is inherent and easy; the cairns serve no purpose. The National Park Service forbids building cairns on trails such as this; it disturbs the natural fall of rocks and soil, and at scale, it causes erosion. To me, these are tiny towers of willful ignorance every few feet.

Why, I think. Why, why, why.

I come across a cairn that is massive and intricate, three times the height of the others. A castle, more than a cairn. Still looking down, I knock it over with gusto. It holds the same pleasure as knocking down something made of building blocks. It’s a starting-anew.

I feel eyes. I look up for the first time in a long time and stop dead in my tracks, the destroyed cairn at my feet.

There, about 15 yards in front of me, is a man the size of an NFL linebacker. He is broad and bucking-bull-shouldered with a look of steel that permeates me to my core. His skin is sandalwood brown, his braided hair shines coal black in the rays of sun reaching between the pines, and he’s blocking the trail.

A girl stands behind one of the pine trees on the trail, a few feet from his protection. Her left side is facing me, and she must be 10 or 11. She is his child; it’s evident. She too is broad, a small carbon copy, but feminine. She hovers behind the tree; she is intentionally not making eye contact with me.

Frozen in place, she holds a pocket knife high and parallel to the ground, clearly carving into the backside of the tree. Her second hand is cupped around the knife, but the pointed blade is visible. I look back and forth between them, between the stillness of the girl and the immensity of the man.

A beat late, the understanding hits that these two are well within their rights to carve a thousand names into trees, into the rocks, and deep into the thumping heart of what must be their ancestral lands.

“I’m sorry,” I say, sheepish, quiet. I break eye contact and smile out of trained feminine deference as I make a motion forward, waiting a split second. The man steps aside, but his eyes don’t leave me. I walk past. I don’t look back but I do look up. I can almost see the parking lot from where we are.

Four wheels carry me out of the splendor of Glacier National Park into the hills of new-growth pine forests that buffer it. I trade one imaginary border for another. I head east through the Blackfeet Nation — a foreigner on forced, sacred, and sovereign lands — praying for the sort of forgiveness that is both mine and not mine.

I’m in my round pen with my new filly.

She’s big for her age, a bright gold buckskin winter coat is growing in. She’s not yet a looker; she’s in what I’d call “growth proportions.” At 2 years old, she’s somehow gangly and stout at the same time.

She’s a young mustang off the White Mountains Herd Management Area near Rock Springs, Wyoming. Historically, the herd reaches back to the U.S. Cavalry’s stout, old-style thoroughbreds, standardbreds, and stock horses. She looks all of the above, with thick bone in her legs that is somehow not unrefined. Appaloosa blood definitively courses through her veins; her white-rimmed eyes and high-contrast striped hooves are a dead giveaway.

She was started on the Honor Farm, a Wyoming correctional facility that teaches inmates life skills like colt-starting. They have a lauded horsemanship program, but most of the inmates are beginners. So I’ve decided to go back to basics with Seven, as I’ve called her.

Round and round she goes. She turns her head to the outside of the fence, arcs her body away from me. She tries to stop at the gate. Her jaw is tight, her head high. She’s telling me something: I don’t want to be with you. And I’d like to leave this round pen.

A dark storm of tension builds in her as she holds her breath and turns her very existence away from me. I watch it envelop her, the golden light of her buckskin coat peeking through the clouds.

So I stop asking for movement. Most horses will lick and chew at this point, releasing their tension. She doesn’t release. She holds tight, a distant cold look in her eye, her head cocked away from me.

I step forward toward her. She swings her head in my direction. I step back.

I am listening, I tell her with these subtle movements. I won’t put pressure on you that you can’t handle.

I step forward again. She swings again, hard and definitive. I listen, moving backwards.

This time, her eyes change. She looks at me, curious. I see a sparkle of recognition. I take another step back, offering her room and time to think.

On this, the little gold horse takes a deep breath, then sighs out briefly. Her breath leaves only fog on cold air, but we’re getting somewhere.

I move all the way back to the edge of the pen, releasing every ounce of physical pressure I can muster. She follows me for the first time; we reach the end of the pen together. When I stop, she presses her head into my chest, breathes in all the static energy between us, and then yawns as wide as her jaw will let her. She does it once more. On her exhale, a billowing cumulonimbus cloud wraps around both of us, then rises. For a fleeting moment, it towers thousands of feet in the big blue Montana sky.

Then, it’s gone. The storm releases entirely from both her wild golden mind and her growing golden chest. She hasn’t swung her head at me since.

I’ve been in Todos Santos, Mexico for a few days now, staying alone in a hostel tucked in the back edges of a neighborhood where mutts without collars nap luxuriously outside homes they may or may not belong to.

My Spanish is passable, enough to get by. I can go to the neighborhood mercado and buy fresh chicken, tortillas, avocados, limes, and rice. This is the dinner that I cook for myself over and over again in the shared kitchen. Simple, easy, good enough for me.

I play a game of barefoot soccer with kids in the street and our laughter breaks the silence of the midday heat. I walk backroads to the nearest beach, where I whisper hellos and how-are-yous to an obese bay horse tied to a palm tree, nickering at me across the brush. I sit at the beach, empty of tourists, and the waves roll so heavy and vengeful against the berm of sand I hardly dare to get my feet wet.

Swaying in the hammock, reading a book, I’m interrupted by a mariachi band in formal white embroidered dress. They walk the street playing their lilting harmonies and stop at the house next door to the hostel. I roll out of the hammock and peer through the fence, enamored by melody.

On another walk around town, I run into a few people I met at a dinner hosted by the hostel’s caretakers. They invite me to dinner and a rooftop movie screening. I walk home at 1 a.m., and the town is thick with alcohol and the hazy tensions that intoxication ties into the air.

I’m nearly home, just a few blocks away, and a rowdy group of younger guys loiters on the sidewalks looking for any kind of time. I can hear words that I barely understand and they begin to worry me, but I have to keep going. Suddenly, their words turn to no words, and my hand breezes over something sleek and soft.

I look down. At my side is a stark white bully dog with a head the size of a pumpkin. His back stands tall at the base of my swinging fingertips; he’s at least 100 pounds, not an ounce of fat on his muscular body.

More importantly, he is matching every step to mine.

I rest my hand on his broad, muscular back. People step aside as he escorts me through the throng and around the corner to the other side of the street. I reach down to pet him and thank him for the walk, but I touch only air.

I turn around. I peek down the alley, through the leaves of palms that skirt a restaurant patio, down the street, back up again.

He’s gone.

Five miles into Yellowstone, it’s a clear-as-glass day up Slough Creek, where the glacial water is numbing cold, even in mid-July.

I’m standing waist-high off the creek’s edge, thinking about the big native cutthroat trout I see under the towering rock about 20 yards from me and how I might catch them. I haven’t rigged my fly rod, but I’m planning on it. My friends are fishing upstream from me and they seem to be locking into a few.

This is the longest hike I’ve done since four knee surgeries that ended with two bionic implants. The heat in my joints is still present, even a year later, but I feel good if not out of shape for the 10-mile day, only half-finished. Soaking in winter’s excess numbs whatever heat is circulating in my new knees, anyway.

Above me, a bison walks the cutbank of the river. The big bull stumbles down an eroding ledge with zero grace, where he takes a long drink while simultaneously pissing in the water. I’m downstream, but on the opposite bank. No bison pee-warmth over here. No drinking this water without boiling it, either.

Below me, two minuscule parr fry begin a game. Sitting in the current, one of the baby trout races over, touches my leg, and bounces back. Then, the other does the same. I grin at this spectacle, remembering games of bravery tag played with my own little sister.

After a few minutes of this game apparent, the two minnows are chased off. Two larger juveniles swim over, a little more brazen, glide through my legs, bump against me, swim away, then back.

The curiosity of this new, current-breaking human structure pulls the fish in. The bigger trout chase off the smaller trout, and after a half-hour of total submerged stillness from the waist down, at least a dozen trout have bounced off my legs. Then, a 14-inch cutthroat saunters over and makes a new home between my ankles, staving off the current, the weave of her body touching my own every now and then.

After an eternity, she chooses to leave the safety of my ankles and elegantly glides back under the rock, swimming in place with her pals.

I step out of the glacial pool and my legs nearly collapse, numb from the water I’ve been in for over 40 minutes, enthralled with this weird and curious sport of cutties.

“Are you going to fish?” My friend Elise calls from the other bank, the bison long gone. I don’t think so, I tell her. Not today. I lean back, close my eyes, and lay in the heat of the summer sun.

On the hike out, the first smoke of the summer rolls in over the Gallatins, the Absarokas, and the Beartooths. It sets so heavy into the sky that we lose the edges of the mountains by the time we get back to the cars.

Over the next few weeks, the water temperatures rise so quickly and devastatingly across Montana that I choose not to fish for the rest of the summer. The smoke sticks around until the depths of September.

I am not an exceptional swimmer, but I’ll snorkel all day. With fins lazily lolling, I make my way toward Isla Espíritu Santo and slowly enter a cave our tour guide has pointed out.

The water is crystal blue once inside, quieted from the currents, about 25 feet deep. Just as I think nothing is going to happen, she glides with her back against the sand below me. I am now near the back of the cave; I turn and the young sea lion turns with me.

She begins to rise, her eyes infant-like in their enormity and child-like in her mischief. She blows giant bubbles that hit me in the face; they rise like the foam of a freshly poured Guinness. She stays right there, below me, belly up, matching my pace. I could reach out and touch her, but I am floating, watching, waiting.

This mammalian mermaid is who I came to visit, though I didn’t think it would happen like this. Prior to entering the cave, a few adult sea lions had danced around us below the water, but this is different. My new friend rolls away from me and begins darting around like a puppy with a tucked butt, ripping and running circles until exhaustion hits.

As I exit the cave, I feel pulls on my flippers, the same weight I feel on my snowshoes when my border collie gets tired and tries to melt into my heels as he does on hiking trails.

My human friends beyond the cave are laughing. My aquatic friend follows my slow current, trying to hitch a ride on my plastic flippers. She finally spins off them, makes one smirky, belly-up turn below me, and darts off back to the island, to mother, to siblings, to safety, to whatever it is she must do with the rest of her time.

At Kristen’s horse show, I bear witness to a transformation of the most elegant kind. It’s a balm against the heifer that didn’t make it and the calf that likely didn’t either.

I've ridden Kristen’s horse, Commander, on trails in his winter fluff near her home. At the show, he’s shaved down to a horsey buzz cut in his entirety. Before her class, we pick sawdust from the pale tan of his body-clipped bay coat until he’s clean as a whistle. My fingernails go black at the edges from untangling the minutiae of his glorious tail, banged straight across the edge for clean lines, thick with shining agents and black pigment to stamp out the sun-bleached hairs.

My trail-riding friends step into the ring. Together, the classically trained pair becomes air, light, and wind. Commander’s toes spend more time in suspension than in the sand. For five minutes, they’re elegance afoot, sleek and smooth, a visual contrast of gleaming sienna and coal-black in motion against the bland winter gray of the day.

The team takes second place in the Grand Prix level of dressage, the highest any dressage rider can aspire to. It’s Olympic-level riding, a partnered progression over years of discipline. The next day, they’ll win it.

My stomach sinks as I leave, heading back toward the corner of birth and death. I pass horse trailers, fussy women prodding their own giant warmbloods to perfection, white-britched girls running for the snack trailer, their Welsh ponies left behind, tied and waiting. I pass barn after barn, then a giant grass-green field filled with cross-country jumps.

The farm turns into the neighboring cattle ranch at a single fenceline. I pass the herd of expectant mothers nosing at round bales, no calves at their sides. I hold my breath and jam sadness into the bottom of my guts.

Then, I see them.

A black Angus heifer walks the fence edge with a teetering calf on her heels. Just a few hours old.

Nicole Qualtieri is the Editor-in-Chief of The Westrn. She’s written for Outside Magazine, USA Today, GearJunkie, MeatEater, Modern Huntsman, Backcountry Journal, Impact Journal, and many others. A lifelong horsewoman and DIY outdoorswoman, Nicole lives on the outskirts of Anaconda, MT with a full pack of happy critters.

The Westrn is a collective of three professional journalists focused on unearthing great outdoor narratives. In addition to two long reads per month, we’re publishing our first quarterly newspaper on April 1, 2025.

Purchasing an annual subscription through Substack means you’ll receive four issues of the paper in addition to our digital work. Get 20% off before March 20 here, or pre-order a single issue for only $8 here.

I got the notification for this hours and hours ago and saved it for the very end of the day because oh boy, Nicole Qualtieri wrote a new thing, I better be READY to SIT DOWN and ABSORB it and CONCENTRATE on it.

I loved every word of this, Nicole! Somehow the world sure does just happen that way, doesn't it? 💙

Really love the winding nature of this, the vignettes. And as a woman new to horses it’s thrilling to get a little taste of what having these animals in my life will be like.