Rue Mapp Wants to Connect

The founder of Outdoor Afro believes 2025 is a great year to find joy outside together.

The Interview is a print-to-digital series that publishes in The Westrn’s quarterly newspaper. Purchase copies of the inaugural issue here.

Rue Mapp started Outdoor Afro from her kitchen table in Oakland, California in 2009. Sixteen years later, she has transformed both her personal brand and her not-for-profit into household names in the outdoors industry.

From collaborations with MeatEater, Venus Williams, CLIF Bar, REI, and others, to a coffee table book dedicated to platforming Black joy in nature, to a nationwide programmatic network over 60,000 participants strong, Mapp has redefined what it means to be a leader in the outdoors over the last decade and a half.

Today, community organizations like Outdoor Afro stand as beacons of hope for outdoorspeople who see a diminishing emphasis on representation from the various agencies stewarding their public lands and waters. Mapp never aimed for Outdoor Afro to be a diversity organization, she says.

But it’s hard to ignore how the organization’s mission — to celebrate and inspire Black connections and leadership in nature — fills a gaping hole left behind by the federal government’s recent divestment from diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives across the outdoors spectrum. If there’s ever been a time to reemphasize that everyone belongs outside, the time is now — and Mapp is taking that on one swimming lesson, fishing trip, hike, and paddle at a time.

As a board member for sporting and conservation organizations like the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership and The Wilderness Society, Mapp also has seats at a variety of tables. This year, she plans to use those platforms to build as many human connections as possible — something we all could use a little more of right now.

Mapp joined us for a conversation from her home in Oakland.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

The Westrn: How did the outdoors factor into your childhood?

Rue Mapp: I grew up in a hybrid of the city and the country. I spent weekends on our family’s farm, and longer stretches in the summertime. For years, we didn't have a telephone up there or even a TV. So all you could do was just be outside and be in dirt. My dad was at his happiest there.

My dad grew up in the Jim Crow South, so he knew firsthand what segregation was all about. I now understand that he was intent on creating his own welcoming space for family and community.

Not only do we have all the farm happenings — it's a hobby farm, so we're talking like 15 acres, right? We had cows and pigs and great gardens — but my dad was also intent on creating opportunities for outdoor recreation. Because of that, we had a pool, and he built us a tennis court.

It was fantastic to grow up in a place that offered this range of outdoor engagement. Rest, recreation, and hospitality are in my soul because of those experiences, and they happened within my family and my community. That's why I started Outdoor Afro.

Those values sit at the heart of what we do, to this day.

TW: Do you have a favorite spot on public land, either close to home or far away?

RM: I was just outside of Lander, Wyoming last fall for a pronghorn hunt, and it was phenomenal being there. It’s iconic and vast. But lately, I’ve been thinking about the lands that are hiding in plain sight where big populations live. I think they’re just as special as these more wild public lands that are often the first to come to mind.

I serve on the board of The Wilderness Society and the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. In those rooms, there's a lot of conversation about public land. If you’re not equipped with the right information, those spaces can feel full of insider baseball. They contrast with the experiences of most people I interact with on a day-to-day basis and even within my own organization. If you asked them about public lands, they might not know what you’re talking about. Because of this, I've been trying to think about the right altitude at which to talk about lands that are available to the public.

In my experience, most people need some basic help just defining public land. Are they places that are free? Far away? It can get really confusing. So I'll try to identify places that people know about, and reframe those places as public lands. We’re talking city parks, public soccer fields, community gardens, and other places like those.

Personally, I love Lake Merritt in Oakland, California. It's right in the middle of the city and it's the oldest wildlife sanctuary in the country. And people don't know that at first, but then it starts to click for them: Oh, that's public land, and it’s also wildlife habitat.

This year, I want to spend some more time talking with people about our natural resources, how they'll be utilized going forward, and why that matters to all of us. I want to open up the aperture and conversation about what public lands look like and how they really do matter to everybody in some capacity, no matter how small.

TW: You were a fashion designer before you started Outdoor Afro. How has that influenced the work you’re doing now?

RM: Fashion was my first business. My mom was a seamstress. We always had tons of fabric around, so I was able to experiment a lot with different textiles and pattern-making. By the time I was 12, I was making all my own school clothes. I put ads in high school newspapers so I could make prom dresses.

I turned that passion into a business in my early 20s. When I lived in San Francisco, I sold small runs of products to boutiques in the Upper Haight. I didn't have any experience with running the business side of things. I was only focused on the creative. I belonged to a collective of designers, and that experience taught me a lot about adding capacity and having partners — people who can do the things you're not necessarily good at. I also learned about the limitations of being both a creative and a businessperson at the same time.

It's not that big of a deal if you're not good at something. It's just an opportunity to build a team or connect with another individual. You can complement one another.

TW: So it was a full circle moment when you and REI teamed up on a hiking apparel line?

RM: Even though I owned a lot of great outdoor gear, it didn’t feel like it represented my personal style. I might be wearing a couple thousand dollars worth of clothing, but I thought I looked like a dumpster fire. I didn't look how I wanted to look in the outdoors.

I wasn't colorful. The fit was not what I wanted it to be. I felt like I was wearing this muted outdoors uniform that you had to wear to be legit.

I had a longstanding relationship with REI for many, many years prior to creating the collection. I decided I was going to make the collection regardless, but I told their team that I'd love to make it with them. We created something really special together for a couple of years. I’ll always be grateful for that.

TW: Are recent efforts to suppress diversity initiatives changing Outdoor Afro’s approach to amplifying Black joy in the outdoors?

RM: I didn't start Outdoor Afro because I cared about diversity in the outdoors. That's how we got pigeonholed from time to time. Really, it was about telling a new narrative about what we can be, what's possible that's not being talked about, and how we can stand on the shoulders of a long history of Black people who love the outdoors in an empowered way, even in the worst of times.

When things feel chaotic or politically charged, I don't take them personally. I just try to stay curious, because fear and curiosity don't mix. Staying curious keeps me in a better heart posture, regardless of what's going on in the world.

I'm thinking about folks who made places of refuge, like inns, resorts, and beaches, at the same time when folks were getting lynched elsewhere. Nature and being in nature was so important that people created those places of purpose and visited them passionately. Some of those places still exist; Martha's Vineyard has a huge history along those lines. I want Outdoor Afro to stand on the shoulders of what I feel is that forgotten history.

By the time we started Outdoor Afro, there was this crazy stereotype that Black people don't do this and we don't do that. And I was like, what? What are you talking about? If you take a walk on Lake Merritt [in Oakland], it looks like the United Nations. That’s because people connect best with the outdoors near where they live.

I think, as a society, we define the outdoors too narrowly. We look in the wrong places and for the wrong activities. If people are connecting to their wild, it’s going to look different in different places. This ties back into what we mean when we talk about public lands. Sometimes our language is just not good enough to describe what's really going on.

TW: How are you navigating what has been a trying time for much of the outdoors-loving community?

RM: As weird of a time as this might be, I'm feeling more space to push people to just say exactly what they want and what they mean to say. Let's talk about the values. Let's talk about what we care about, right? Because if we do that, we're going to find we have a lot more in common with others than we have differences.

Every year at Outdoor Afro, we pick a grounding, galvanizing word. This year's word is “connection.” In 2025, I am a heat-seeking missile looking for connection with everybody. Bring your connection to the table. I'm ready for it.

I love this work so much because it's an easy entry into the possibility of connecting. Nature is an open-source platform, and there's no one you can talk to that doesn't have something special about their connection to the outdoors. Sometimes, you have to tease it out, right? Because like I said, sometimes people are like, well, I don't like to camp. I don't like to hike or hunt or dangle off the side of a cliff.

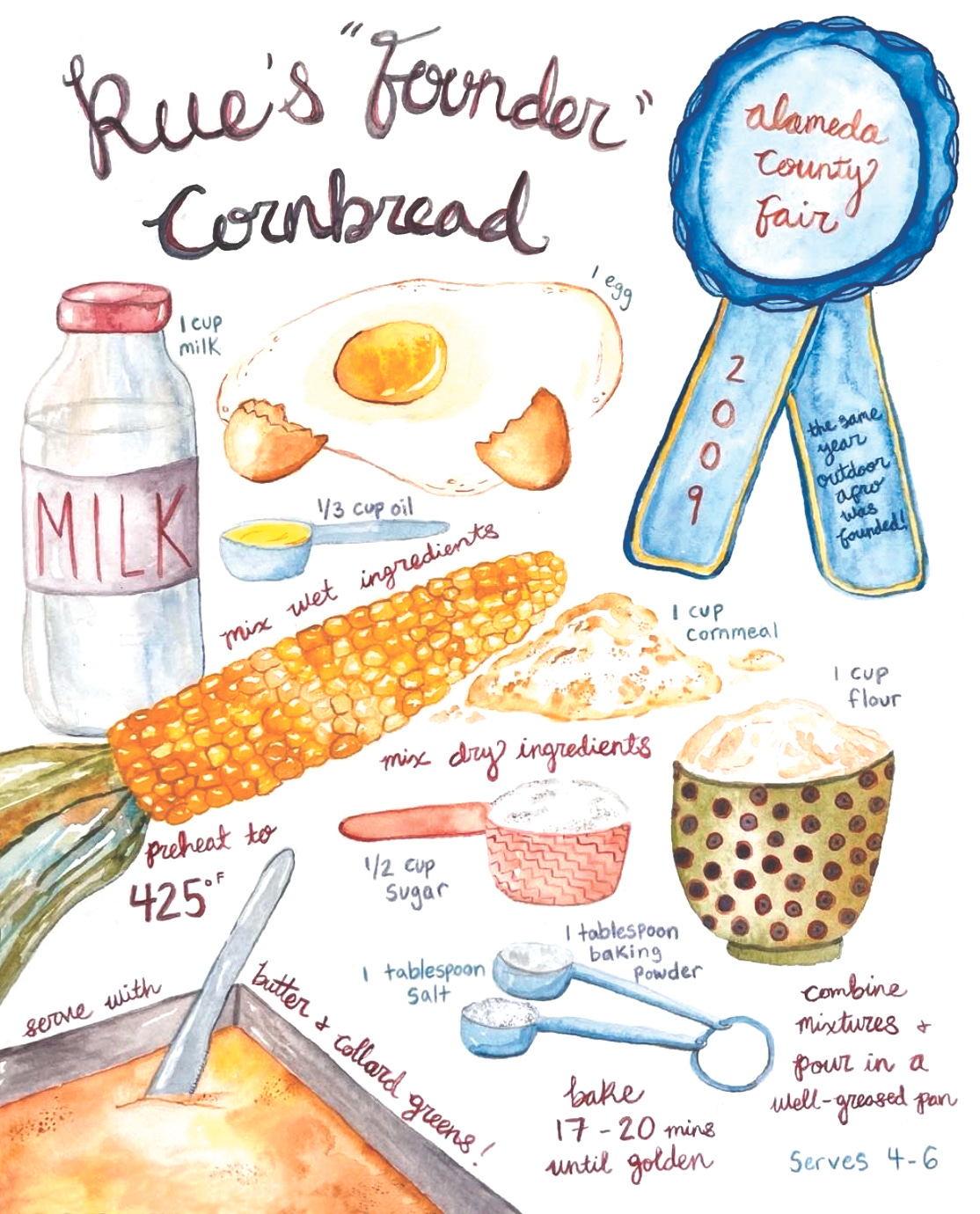

But do you like to go outside and have a picnic? Do you like to go for a stroll along a lazy lake? It’s okay to like nature in a more comfortable way. Personally, I love outdoor comfort. Do you like festivals? Do you go to the crafts fair? Do you go to the county fair? I love county fairs. Back in 2008, I entered my cornbread in the Alameda County Fair and I won a ribbon. Isn’t that also connecting to nature, the community, and the outdoors?

That’s my pro tip for Thanksgiving dressing, by the way.

Really, I'm a woman of faith. That's how my life is both navigated and governed, no matter what is going on. I don't commingle my politics with my faith. That's key. My faith gives me a deep joy inside, a fortitude, and — most importantly — a bigger picture perspective about the current state of the world.

Not long ago, Black people and particularly Black women had very few choices for what they could do for a living. My grandmother was a domestic. If you went back in time and told her that her granddaughter would oversee a national organization and that she’d have this kind of impact on the world, she'd think you were nuts. It would be the wildest dream you could put at her feet.

I'm present to that every single day. I'm not talking about an expansive time frame; I'm talking about my grandmother who was alive just two generations ago. That's a stone's throw from today. In less than two generations, I have become her wildest dream. How am I living up to that? Where can I find the complaint in that?

Through their Making Waves program, Outdoor Afro is on a mission to teach Black children and caregivers to swim. Learn more here about the organization’s work here.